Three of the Best Live Albums Ever…

The wall never had a chance. In October 1984, Tom Petty stared at yet another mixing board in yet another sterile Los Angeles studio, listening to the same “Southern Accents” tracks he’d been wrestling with for two damn years. The cocaine wasn’t helping. The pressure wasn’t helping. The fact that he’d spent a small fortune trying to capture some elusive artistic vision that seemed to slip further away with every overdub wasn’t helping at all. So he did what any reasonable person would do: he slammed his left hand against the studio wall with such force that he completely mangled it.

‘Doctors said he might never play guitar again,’ recalls Stan Lynch, the Heartbreakers’ drummer at the time. The irony was almost too perfect—rock’s most authentic voice of that moment, silenced by his own quest for artistic perfection. Eight months later, Petty stood on the stage of Los Angeles’ art-deco Wiltern Theatre, that same hand wrapped around the neck of his Rickenbacker, playing as if his life depended on it. Which in many ways it did. The resulting album, “Pack Up the Plantation: Live!,” would become more than just a concert recording—it was proof that sometimes you have to completely break before you can heal.

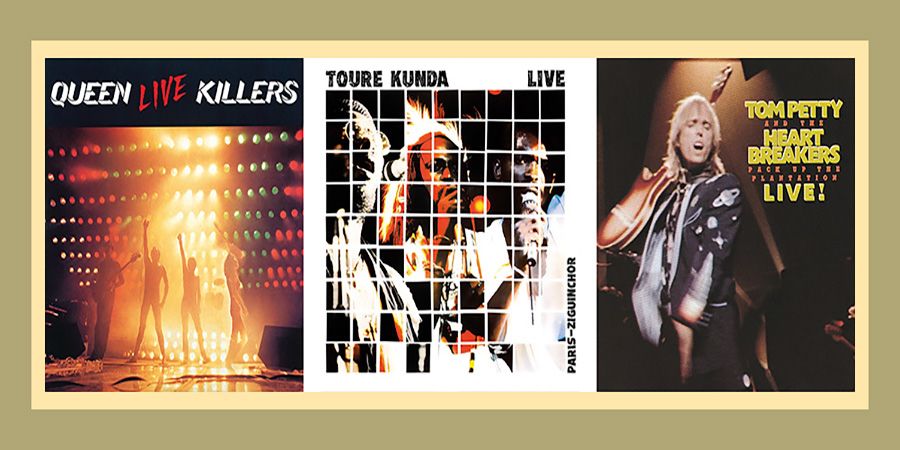

It’s also one of three live albums from the early ’80s that, in my opinion, represent the absolute pinnacle of what live recordings can achieve. Alongside Queen’s “Live Killers” (1979) and Touré Kunda’s “Live: Paris-Ziguinchor” (1984), Petty’s live statement forms a holy trinity of albums, in my record collection, that prove something crucial: when bands find themselves at breaking points—creatively, emotionally, spiritually—live performance can become their salvation.

These aren’t random choices. Each album was selected based on four important criteria: the undeniable quality of the musical performances, the tangible live energy that still practically leaps from the speakers decades later, the extraordinary craftsmanship that transforms good bands into the best live bands, and most importantly: how each recording adds something essential to their makers’ catalogs that no studio album could have provided. At a time when live albums were often viewed as contractual obligations or emergency solutions, these three prove that the format, at its best, can capture something studio wizardry never could: the sound of people pushing themselves beyond their perceived limits.

The timing was no coincidence. The years between 1979 and 1985 represented a sweet spot in rock history—after punk had torn down the rock establishment, but before MTV would reshape everything into digestible visual nuggets. Recording technology had finally evolved to capture the full spectrum of a live performance, while arena rock culture reached its absolute peak. These were the last death throes of an era when a band’s reputation lived or died on their ability to move a crowd, night after night, city after city.

But more than that, each of these albums documents bands at crucial transition moments—moments when everything they thought they knew about themselves was being challenged. For Petty, it was the struggle between artistic ambition and roots-rock authenticity. For Queen, it was the tension between the progressive, vaudeville-leaning complexity of their first three albums and the anthemic power of “News of the World” that would catapult them into superstardom forever. For Touré Kunda, it was the heartbreaking challenge of carrying on after losing their spiritual leader and eldest brother. What emerges from these recordings isn’t just great music—it’s the sound of resilience itself.

The Plantation Sessions

If you want to understand what Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers were at their core, you only need to listen to their version of “Shout” on “Pack Up the Plantation.” What the Isley Brothers intended in 1959 as a gospel-like outburst, Petty and his men turn into something that sounds like it comes straight from his heart, and in the best possible way. It’s not just a cover. It’s a statement of intent, a manifesto in nearly ten minutes of rock ‘n’ roll that grows into an epic jam. Recorded at the Richfield Coliseum in Ohio in 1983, their version slowly builds to something that sounds like it comes directly from Petty’s heart, and in the best possible way. Mike Campbell’s guitar bites and claws, Stan Lynch’s drums pound like a heart on the verge of exploding, and Petty himself—Jesus, Petty sings as if his life depends on it. Which it did. ‘Tom sounds passionate and impressive when he sinks his teeth into his early songs,’ Jimmy Guterman once wrote, ‘and the Heartbreakers are an undeniably great band.’ But that still doesn’t explain the pure alchemy that takes place on this album, the way a band that had just returned from the brink suddenly sounded like they’d rediscovered why they started in the first place.

Take “Needles and Pins.” Most of us knew it as a relatively tame pop song by Smokie, but in the hands of Petty and Stevie Nicks, who came by especially for these recordings, it’s transformed into a true rock classic. Nicks’ harmony on the chorus adds a layer of melancholy that lifts the song to a completely different level, while Petty’s interpretation saturates every line with an urgency the original never had, and all in just 2 minutes and 25 seconds.

This is why “Pack Up the Plantation” is more than just a live album—it’s the sound of a band finding itself again. Petty didn’t just live rock ‘n’ roll, he breathed it, he was it. And that band behind him? Pure magic. But the real secret of this album lies in something no studio can ever reproduce: the building anticipation of an audience growing increasingly eager to participate in the experience. You hear it building from song to song, this collective energy growing to the point where thousands of voices merge with Petty’s. On “Refugee,” the audience practically becomes an extra band member, their voices so loud and so perfectly in sync that you can only think: damn, I wish I’d been there. These are the concerts everyone wished they’d been at, where the line between performer and audience completely disappears. It’s the sound of a community forming around three chords and the truth.

Killer Queen’s Last Dance

If Tom Petty in 1985 was trying to find what he’d lost, then Queen’s “Live Killers” documents a band that didn’t even know they were going to lose anything. Recorded between January and March 1979 during their Jazz tour through Europe, the album captures Queen at the absolute height of their rock powers, at the last moment before they would transform from hungry rockers into unreachable megastars. The irony is that the band members themselves hated the album. ‘The only thing live about Live Killers is the bass drum,’ drummer Roger Taylor later joked, a not-so-subtle reference to how much studio magic was used to save the recordings. Guitarist Brian May was equally dissatisfied with the final mix, which the band had done themselves in their own Mountain Studios in Montreux.

But sometimes the power of a recording lies not in technical perfection, but in capturing a moment that will never return. And “Live Killers” does exactly that—it preserves for eternity the sound of four men who still believed they could conquer the world by simply being harder, smarter, and more theatrical than everyone else. Nowhere is this clearer than during “Brighton Rock,” where May’s guitar solo grows into a twelve-minute showcase of pure virtuosity. With his characteristic delay effects, he creates layers of sound that feel like they’re coming from space, while Freddie Mercury conducts the audience as if he’s the maestro of the world’s greatest orchestra. It’s arrogant, it’s bombastic, it’s exactly why we loved Queen before we all knew we did. To achieve that, Mercury first had to die, unfortunately.

The real heart of “Live Killers” beats in “Spread Your Wings,” a song that shows in everything why Queen was so damn good. Mercury’s voice radiates pure power, every word saturated with the conviction of a man who knows he’s creating something special. And when the audience starts singing along, when thousands of voices come together in perfect harmony, that’s the moment when you understand what rock ‘n’ roll really means. For those lucky enough to experience this live, this track is forever etched in memory. It’s goosebumps in their purest form.

“Live Killers” has many such moments: “Love of My Life,” where what began as a tender ballad is transformed into something much more powerful, a dialogue between artist and audience that was so perfect that Queen still recreates it today. Thousands of voices coming together in perfect harmony, taking over Mercury’s words as if it’s a collective prayer. It’s a moment that became so iconic that Brian May still plays it more than forty years later, now with Freddie as a video image beside him on stage. If you’ve ever seen how an entire arena full of people takes over Mercury’s role while his image stands next to May, well, then you know what goosebumps mean. It’s the ultimate confirmation that some moments in music are simply too powerful to die, even when the man who created them did. This was Queen in their purest form: not the flamboyant showmen they would become, but four musicians discovering they had created something bigger than themselves.

African Brothers

Why does a band that’s relatively unknown stand in the same ranks as Tom Petty and Queen? Because sometimes the best stories are the ones you don’t expect to hear.

Touré Kunda, literally ‘the Kunda brothers,’ were already superstars in Senegal when, like so many African artists of that time, they made the crossing to Europe to further build their careers. But where others failed or disappeared into the bureaucracy of the European music industry, the Touré brothers succeeded in creating something new: a multicultural band avant la lettre where the emphasis was on pure musical craftsmanship. And Jesus, what craftsmanship. If you hear the opening of “Live: Paris-Ziguinchor,” the song “Sol Mal”—that percussion that starts like a heartbeat and then grows into something irresistible and brilliant—then you immediately understand why this album must be mentioned here. The band knew, like no other, how to breathe life into the fusion between African music and pop and rock in a way that felt authentic, never forced.

Tragically, this masterpiece was born from grief. In January 1983, the eldest brother, Amadou, died during a concert in Paris. Instead of stopping, Ismaïla and Sixu Tidiane decided to return to Africa as a tribute to their lost brother and spiritual leader.

What followed became an unlikely triumph with a tour throughout Africa. The highlight? Their performance in Ziguinchor, Senegal, the city in the Casamance region where the band originally comes from. A region that was then heavily plagued by rebel violence from the MFDC under the leadership of Abbaye Diamacoune Senghor. And yet, despite all the unrest, President Abdou Diouf decided to go see Touré Kunda there. It became a great reconciliation festival, a moment when music transcended political boundaries. This album represents musical perfection—jazz, pop, rock, and mbalax fused into something that feels like it should have always existed. Listen to “Martyrs” or the live version of their hit “E’mma” and you immediately understand: the world needs more of this music. The result became the blueprint for all world music artists who would later successfully make the transition from Africa to Europe. This concert is so breathtakingly good that it’s impossible to ignore.

A Spirit in a Bottle

What do a man with a broken hand in Los Angeles, four British rockers who hate their mix, and three Senegalese brothers mourning their lost leader have in common? They all prove the same thing: that moments exist in music when everything converges—pain, joy, loss, triumph—and that grows into something greater than the sum of its parts.

These three albums all emerged at breaking points. Petty breaking before healing. Queen is on the verge of changing from hungry rockers to unreachable icons. Touré Kunda has to create something new from the ashes of family tragedy. And in all three cases, it was live performance—that final, pure contact between musician and audience—that brought salvation.

At a time when studio albums were becoming increasingly polished, these recordings showed something else: the raw power of the moment, the perfect imperfection of genuine human connection. You hear it in the way Petty’s audience takes over “Refugee.” You feel it when thousands of voices come together during Queen’s “Spread Your Wings.” You’re moved by the political charge of Touré Kunda’s reconciliation festival in Ziguinchor. This isn’t entertainment, but art. This is what moves people.

These albums represent the last death throes of an era when a band’s reputation lived or died on their ability to move a crowd. Before MTV would change everything into visual bite-sized pieces. Before digital perfection became the standard. These albums captured a spirit in a bottle, that elusive magic that can only arise when musicians and audience surrender to the same moment.

Maybe Tom Petty had to break his hand to understand what he’d had all along. Maybe we needed these albums to remind us why we once fell in love with rock ‘n’ roll. Not because of perfection, but because of the moments when imperfection becomes something magical.

That’s the power of live music. That’s why these albums, decades later, still give us chills. They remind us that music at its best isn’t something you consume, but something you participate in. A conversation between artist and audience that, when everything goes right, transforms into something nobody expected. And sometimes, very rarely, you capture that moment in a recording.

![]()