De Porcaro Doctrine: ‘That’s Jeff on the radio, again’

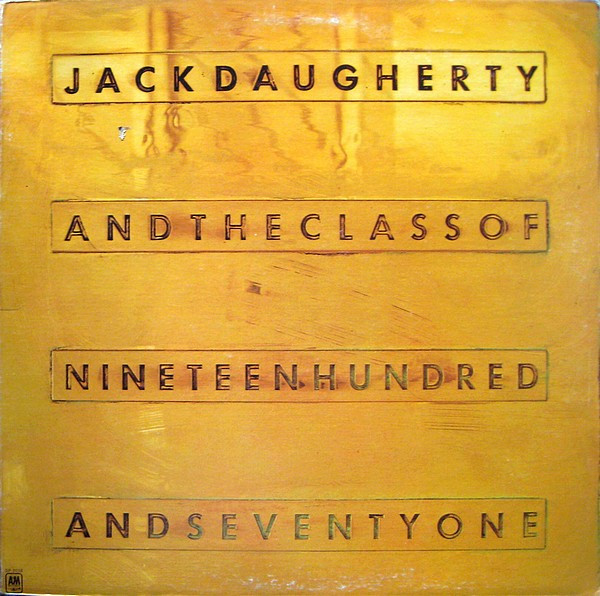

It’s an obscure album: “The Class of Nineteen Hundred and Seventy One” by composer and big band leader Jack Daugherty. The credits list an almost endless array of musicians who contributed to the record, including no fewer than four drummers: Hal Blaine, Jim Keltner, Paul Humphrey and Jeff Porcaro — the beginning of an enormous legacy and an influence on drummers that cannot be overstated. Porcaro died prematurely in 1992 at the age of only 32. More than 32 years after his death, the conclusion is that the legacy he left behind is still of monumental proportions. A tribute.

Four drummers

Four drummers, three of them seasoned professionals, played on that Daugherty record. Hal Blaine, who died in 2019, was already an established name in 1971, one of the most in-demand session drummers who is estimated to have played on more than 150 U.S. hits that reached the Billboard top ten. Jim Keltner, too, is no stranger. His drumming can be heard on the successful “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” by Joe Cocker, even though Keltner is a jazz drummer by origin. Paul Humphrey, who died in 2014, was a true jazz drummer, remained loyal to the genre, and played for Wes Montgomery, John Coltrane, and Mingus. In 1971, Humphrey was 35 years old. The odd one out on Daugherty’s album was Jeff Porcaro, who was seventeen.

Speed-dial

Jeff Porcaro was groomed by his father at a young age for the big leagues, which arrived swiftly after Daugherty. Donald Fagen of Steely Dan asked him to drum on a few tracks on “Pretzel Logic”, followed by the album “Katy Lied”, on which Porcaro played all the tracks. Then came Jackson Browne, Leo Sayer, Boz Scaggs, Eric Carmen, Hall & Oates, Lee “Captain Fingers” Ritenour, and Diana Ross. In 1977, he recorded albums with all of the aforementioned artists. It made him one of the most sought-after session drummers early in his career.

Porcaro’s influence cannot be overstated, but it’s an influence that unfolded in complete anonymity during his lifetime. Perhaps it’s precisely for that reason that he was asked to play on almost everything, including “Thriller” by Michael Jackson and even Pink Floyd’s “The Wall”, where he replaced Nick Mason on “Mother”. His ego never stood in the way — not with Jackson, not with Roger Waters. Anonymity brought him work — lots of it. That’s why chances are high that there’s an album in any record collection with Porcaro’s fingerprint on it, without the listener knowing they’re hearing the Toto drummer: the Porcaro Doctrine.

It’s a legacy that, as is often the case with legacies, also has a very ugly side. In 2018, the drummer’s widow sued Toto co-founders Steve Lukather and David Paich over royalties. It leaves a sour taste to the genius that Jeff Porcaro was. But Susan Porcaro-Goings wasn’t entirely wrong: without her husband, Toto would never have existed, while the band, with only Steve Lukather and Joseph Williams as original members, is still touring. The final leg of the “Dogz of Oz” tour in the U.S. is about to begin.

The Drum Doctor

In a blog titled “The Drum Doctor”, the author, Nick Lauro, puts it perfectly. Fun detail: this “Drum Doctor” divided his development into a few categories, such as “The Birthing Pool” with Deep Purple’s Ian Paice and Phil Rudd from AC/DC, and “Learning to Crawl” with Big Country’s Mark Brzezicki and Phil Gould from Level 42. But there is also a category called “Hard Lessons”: the serious, difficult lessons are attributed to Porcaro, who is placed alongside John Bonham of Led Zeppelin. Regarding Porcaro, Lauro describes his feeling after August 5, 1992: a shock in the fresh awareness that the world had prematurely lost one of the greatest session musicians of the last twenty years.

A session musician. Not the drummer of Toto, but one of the greatest session musicians. That’s what Porcaro was for many in the music industry, with unmatched technique. Lauro writes that he was familiar with Toto’s albums, but ‘only after his death did I realise how often I must have heard him anonymously on the radio. (…) If Toto wasn’t on tour, his phone number must have been on the speed-dial of every Grammy-nominated producer on the planet.’ The complete catalogue of session work can be found at https://www.frontiernet.net/~cybraria/. The list is impressive.

The Porcaro Groove

But how big was Porcaro’s influence? It’s not only defined by the vast number of songs he drummed on, including the work with his band. No, it’s also — and especially — defined by the fact that the drummer developed a unique style and was eager to share it: the Porcaro Groove. The secret: the sixteenth note on the hi-hat played with one hand — nearly impossible for most drummers. It’s a technique that was part of the “pocket”, where the feel is far more important than the actual rhythm. The pocket defines the groove. A crucial element in that pocket is the short roll before the actual snare hit: the “ghost notes”. Not a simple tap, but a soft roll, combined with exceptional hi-hat technique. All of this, at varying speeds, forms the foundation of the Porcaro Groove.

Lido Shuffle

That “pocket” became crucial to the sound of Toto — perhaps even more so than the guitar of Steve Lukather or the keys of David Paich (as mentioned, Susan Porcaro-Goings had a point trying to enforce this in court). Porcaro met both men through session work for Boz Scaggs, particularly during their collaboration on “Silk Degrees”, for which Paich wrote “Lido Shuffle”. Porcaro delivered the drums, including the “pocket”. By the time Toto released its debut album, Porcaro had already refined that “pocket” further. A good example is “Georgy Porgy”: it’s a simple four-four beat, but it grooves thanks to that one-handed 16th.

The drummer would continue to develop and perfect his style and technique. Listen to “These Chains” on “The Seventh One”. Or “Lady Love Me (One More Time)” by George Benson. Songs made by the Porcaro Groove — songs that fall apart without it.

It takes some practice to recognise that sixteenth note, in combination with the ghost notes on the snare drum. But once you hear it, you begin to recognise how many songs Porcaro played on. You begin to hear the “pocket”. And there are surprises. For example, on “Chicago 17”, the band’s drummer, Danny Seraphine, was replaced by Porcaro on one track — the hit single “Stay the Night”. The album “Behind the Sun” by Eric Clapton was produced by Phil Collins, but the drums on the single “Forever Man” were played by Porcaro. Compare the studio version of “Forever Man” to the live version on “Live from Madison Square Garden” with Ian Thomas behind the drum kit. The difference lies in a different hi-hat count.

Jazz

Porcaro’s style is the style of a jazz drummer. You could take Jeff Porcaro — who cited Jimi Hendrix as his greatest influence — out of jazz, but you couldn’t take the jazz out of Porcaro. So the big question is: where did that technique come from?

To understand Porcaro’s technique, we indeed have to look at jazz drummers. You can’t avoid mentioning one of the most controversial drummers of all time: Buddy Rich. Rich’s technical skills, combined with speed and flawless timing, made him a major influence on many drummers. That influence is unfortunately overshadowed by the fact that Rich had a notoriously short temper, making him nearly impossible to work with, in stark contrast to Porcaro, who seemed able to work with everyone.

Porcaro surely learned the quick hand movement on the hi-hat by watching and listening to Rich, but other drummers also shaped the Porcaro Groove: funk drummers Clyde Stubblefield, Jabo Starks, and especially Bernard Purdie. The latter is rarely mentioned concerning Porcaro, which is entirely unjustified. Porcaro admired Purdie’s finesse and praised Purdie’s groove in interviews, which became a key ingredient of his style, of perhaps the most famous shuffle in rock: the Rosanna Shuffle. The foundation of “Rosanna” is the Purdie Shuffle: the hi-hat sets the tempo, the bass drum hits on the first beat, the snare on the third. Between the beats, Purdie plays ghost notes.

Bonham and Bo Diddley

Porcaro assembled the Rosanna Shuffle from several elements. The first building block was Purdie’s work on “Home at Last” and “Babylon Sisters” by Steely Dan. The half-time shuffle is the rhythmic base of “Rosanna”. Porcaro combined it with the shuffle Jon Bonham plays on “Fool in the Rain” from the Led Zeppelin album “In Through the Out Door”.

But to find the origins of this rhythm, we have to go back to jazz, to traditional swing. The rhythm stems from how drummers play a shuffle or swing, often with a rolling or triplet pattern by letting the stick produce an extra ghost note between the beats on the snare. By shifting the accents, it feels as though the tempo slows down, without actually slowing.

In “Rosanna”, there’s a third building block: the Bo Diddley beat — a rhythm that goes back to African patterns but became widely known as the “conga beat”. That’s arguably the most important part of the Rosanna Shuffle — that, and the hi-hat technique. A technique that is nearly impossible to replicate. Drummers such as Chad Smith (Red Hot Chili Peppers), Eric Singer (Kiss), and Vinnie Colaiuta have publicly acknowledged Porcaro as a major inspiration. His ability to listen musically, play complex rhythms, and still make the song sound effortless was absolutely in a league of its own. Simon Phillips, who replaced Porcaro in Toto, stated that the band was not looking for someone to imitate Porcaro after his death: that wasn’t even possible, said Phillips.

And that for a drummer who mostly played in anonymity and whose legacy was recognised late, very late. The Porcaro Doctrine is a fact: hearing Porcaro without realising it’s him. Whether it’s Porcaro himself or a drummer influenced by him, and there are many. That brings us back to the words of The Drum Doctor (https://thedrumdoctor.net/inspired/jeff-porcaro): ‘Turn on the radio. If you’re listening to something between 1980 and 2000, you can pretty much bet that at some point, you’ll pause and think: “That’s Jeff on the radio…again.”‘