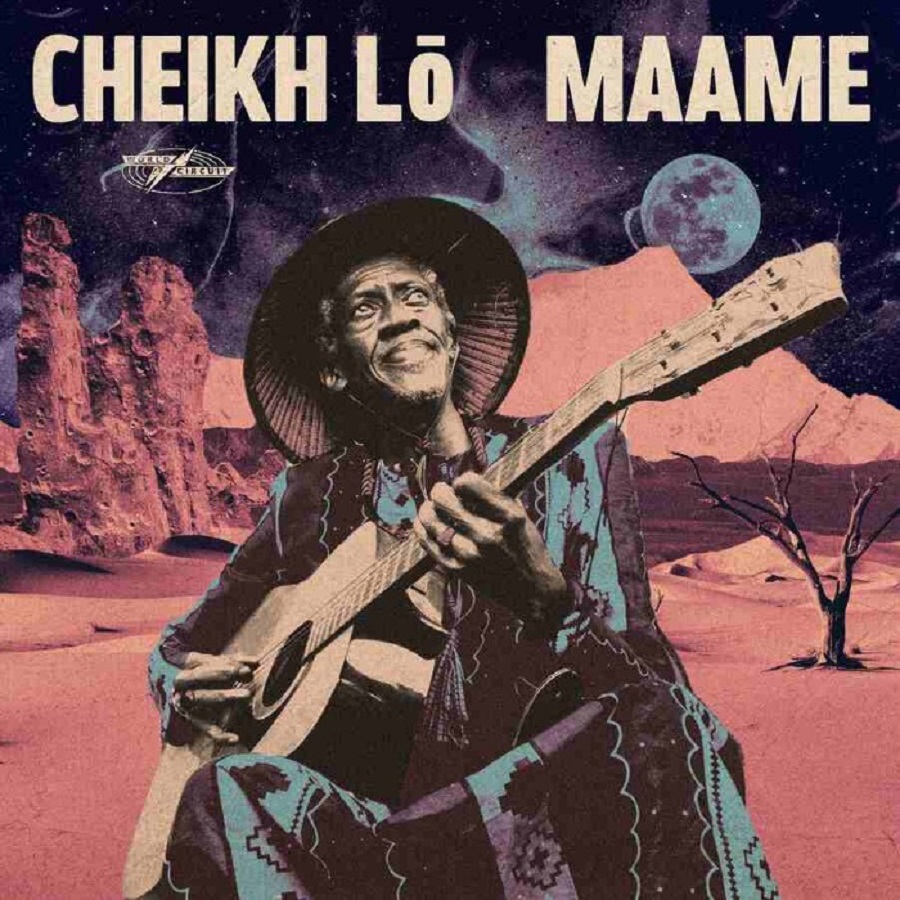

Cheikh Lô – Maame

After ten years of silence, Cheikh Lô returns with an album that grabs you by the throat from the very first note and never lets go. “Maame”, pronounced “mahm” and dedicated to his 150-year-old spiritual guide, is more than just a comeback; it is a spiritual journey through five decades of Senegalese musical history, told by a man whose dreadlocks and kaftans mark him as a devoted Baye Fall, a mystical current within Senegalese Mouridism. At 70, after half a century in music, Lô has created an album that sounds as if his entire life has been leading up to this. This is no nostalgic retrospective; this is a man at the height of his artistic powers.

Make no mistake: this album should have the same impact that Nick Gold’s legendary “Buena Vista Social Club” once had for Cuban music. Gold, who produced four of Lô’s earlier albums before stepping back, helped bring this project to life through BMG, and the result fully justifies his reputation as the man who lifts forgotten musical treasures to global fame. Where “Buena Vista” introduced the world to the timeless elegance of Cuban son, “Maame” opens the door to an even deeper truth: the African roots from which all Caribbean music grew. It was the West African rhythms—the complex polyrhythms of the Wolof, the hypnotic trance of the Mandinka—that crossed the Atlantic in the dark holds of slave ships and later resurfaced as salsa, rumba, and son. In Lô’s hands, the circle is completed; we hear not only how the music was, but how it was always meant to sound.

The story of Cheikh Lô is inseparable from that of Youssou N’Dour, the king of mbalax who discovered him in the late 1980s as a session musician. ‘Whenever he sang backing vocals, I was overwhelmed by his voice,’ N’Dour later recalled. ‘I heard his cassette “Doxandeme” and thought: wow, I found something in his voice that sounded like a journey through Burkina, Niger, and Mali.’ That discovery proved decisive: in 1995, N’Dour produced Lô’s breakthrough album “Ne La Thiass” at his Xippi Studio in Dakar, launching a career that would forever change Senegalese music. But while N’Dour put mbalax on the world map, Lô went further. He became the alchemist who not only blended Senegalese rhythms with Cuban son and Congolese rumba, but also revealed the deeper spiritual connections between these traditions. Born in 1955 in Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, he grew up at the cultural crossroads where the musical traditions of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Senegal meet. That multilingual upbringing—he speaks fluent Bambara, Wolof, and French—laid the foundation for his unique sound, in which borders blur and continents meet.

Listen to the opening track “Baba Moussa BP 120” and you hear the history of Black music in all its tragic beauty. The title itself tells a personal story: Baba Moussa was Lô’s father, and BP 120 refers to his post office box in Bobo Dioulasso. Lô himself describes the music perfectly: ‘Congolese rumba at the start, Cuban salsa at the end—it’s a journey from Kinshasa to Havana.’ What he describes is the cyclical journey of rhythms that began centuries ago in the villages of Senegal, Mali, and Guinea. The asymmetrical rhythmic patterns that we now associate with salsa and son—syncopated accents and polyrhythmic layers that Western ears find so exotic—are directly derived from traditional African drumming passed down for generations. When the Spanish and Portuguese shipped hundreds of thousands of West Africans to the Caribbean, they carried little but their memories and their sense of rhythm. On the sugar plantations of Cuba, the coffee fields of Haiti, and the ports of New Orleans, these rhythms lived on, hidden behind Christian hymns, mixed with European melodies, but always retaining that essential African heartbeat. What we know today as son cubano, rumba, and later salsa are survival strategies of a musical tradition that refused to die.

Cheikh Lô understands this like few others. He grew up listening to Tabu Ley Rochereau, the king of Congolese rumba, and absorbed the Cuban records of his older brothers, who danced to “El Pancho Bravo” without understanding a word of Spanish. What struck him was recognition: in those Cuban rhythms he heard echoes of his own Wolof and Mandinka heritage. In his music, he closes the circle—revealing how the music must have sounded before the Atlantic crossing changed everything.

“Maame” was created during the COVID lockdown in Lô’s own Dakar studio, giving the album an intimacy that his earlier, more polished World Circuit productions sometimes lacked. With his son Massamba Lô as sound engineer and co-producer, Cheikh finally made the music he had always envisioned. ‘For me, COVID actually worked,’ he recalls. ‘We had time to work from seven in the evening to three in the morning. Whenever the feeling came, we went to the studio.’ That homely setting is audible in every note. Where earlier albums like “Bambay Gueej” and “Lamp Fall” sometimes suffered from overproduction, “Maame” breathes an organic calm reminiscent of the best session music of the 1970s. Lô plays all the drum parts himself, and you can hear it: the sabar drums sound like they’re in your living room, the tama talking drums whisper in your ear. Nowhere is his mastery clearer than on “African Development”, a reggae anthem that would have made Bob Marley proud. But where Marley’s Pan-Africanism could feel abstract, Lô’s message is urgent and direct. ‘Africa must change its face,’ he sings with the patient authority of a wise elder. ‘It is time to become sovereign after almost 400 years of slavery and colonization.’ At a time when West African nations from Mali to Burkina Faso and Niger are turning away from France toward Russia and China, Lô’s call for real independence feels painfully timely. His words echo the ideals of Thomas Sankara and Patrice Lumumba, revolutionary leaders whose dreams of a united, independent Africa still resonate with the older generation that remembers their speeches. While younger leaders risk getting lost between Chinese loans and Russian mercenaries, Lô offers a third path: true mental decolonization.

Musically, “African Development” is a masterclass in subtlety. The reggae groove is pure and stripped down—the offbeat guitar chords, the deep bassline, the rimshot on the three—but Lô layers in his signature Senegalese percussion without ever sounding forced. It is as if the music itself underlines the message: traditions can coexist harmoniously without losing their identity. For casual listeners, it is simply a sublime piece of music. For those who truly listen, it is a manifesto wrapped in an irresistible groove.

Yet it is “Carte d’identité” that delivers the album’s absolute peak—and that is no small claim on such a rich record. This is world music as it should be: a composition so layered that each listen reveals new details. It opens with a muted guitar rhythm as a foundation for a spellbinding balafon melody, blooming into a horn arrangement that leaves you breathless. The magic lies in the architecture: the talking drums gently lead the sabar percussion, while a pulsing bassline drives a groove so compelling that standing still is impossible. Then, two minutes in, something magical happens. Cheikh calls on his Czech friend Pavel Šmíd for a guitar solo that takes the very definition of ‘jazzy’ to new heights. Šmíd’s playing is a masterclass in restraint—no showing off, just melodic lines winding around the African rhythms like ivy on an ancient tree. And then the trumpet solo. If you ever wondered what Miles Davis would have sounded like had he grown up in Dakar instead of East St. Louis, here is your answer. It’s the kind of musical moment that makes you stop whatever you’re doing and just listen, lost in the beauty of what human creativity can achieve when continents and cultures merge instead of collide. This is Africa embracing the world without losing itself. This is the best African music in twenty years, period.

The album closes with “Koura”, a piece so purely Senegalese it feels like a return to the essence of everything Lô stands for. This is Wolof music in its distilled form, built on rhythms the late percussion legend Doudou Ndiaye Rose would have recognized as authentic. The sabar drums roll like waves on Dakar’s shore, while the balafon sets the melodic base with its swaying pulse. Then the atanteben enters—the ancient West African flute that sounds like wind through bamboo—and suddenly you’re no longer in a studio but by the banks of the Parc National du Djoudj, where pelicans descend gracefully onto the water among the mangroves. Lô blends his voice into this soundscape like just another instrument, not dominant but equal, part of an ancient conversation. The airy female harmonies that accompany him add an almost ethereal layer, voices rising like smoke from a sacred fire, whispers of ancestors blessing this modern rendering of their heritage. It is a dance with no end, because it needs none—music that exists outside time, a meditation in rhythm. “Koura” proves that after fifty years, Cheikh Lô still knows exactly where he comes from. In an album filled with international influences and collaborations, he ends where every great artist must: with himself, with his roots, with the pure magic of his homeland.

Let’s be honest: in an age where world music often collapses into shallow fusion experiments and Spotify-friendly cultural appropriation, “Maame” is a rare gift. This is the best world music album of the past twenty years—a claim I make not lightly but with the conviction of someone who has listened to everything released over the last decades. From Ali Farka Touré to Toumani Diabaté, from Amadou & Mariam to Tinariwen, no one has produced an album as complete, as profound, or as moving as what Cheikh Lô has delivered here. With “Maame”, Lô has not only built his own monument; he has also proven that authenticity and innovation are not mutually exclusive. He shows that one can embrace the world without selling one’s soul, that bridges can be built between cultures without surrendering identity. In a world increasingly torn by tribalism and cultural rigidity, this album offers another way: the open hand instead of the clenched fist, harmony instead of hegemony.

If this were Cheikh Lô’s swansong—which, fortunately, it need not be—he would depart as a king. “Maame” is more than an album; it is a life’s work distilled into 45 minutes of timeless music. It is the kind of masterpiece your children and grandchildren will still talk about, the kind of music that will endure because it belongs not to this moment, but to all time. Cheikh Lô has his monument. And what a monument it is. (9/10) (World Circuit limited)