Toto and Christopher Cross Enchant Düsseldorf

The evening was still cold, yet there was already a strange promise of early spring—like that first note after a long silence, signalling that more is to come. Düsseldorf was packed, incredibly packed, and the Mitsubishi Electric Halle, in operation since 1971, may no longer be truly suited for concerts of this magnitude. Traffic was backed up, one line of cars after another trying to find parking, forcing most visitors to walk kilometres to reach the venue—a pilgrimage to a sanctuary of craftsmanship. It was reminiscent of Bruce Springsteen’s stories about his youth—if you couldn’t afford gas, you walked because nothing mattered more than the music. Perhaps that was the perfect mindset to experience this music—a little exhausted but full of anticipation, just like the best journeys always begin.

On June 4, 1971, Pink Floyd played the very first concert in this hall—it was the “Meddle” era, just before “Dark Side of the Moon” would change their career forever. The people who were there then are now elderly, and even those who came to see their heroes tonight were, for the most part, at an age where they might already carry a senior pass in their pocket. Yet, there was something wonderfully youthful in their eyes—the same look you see in old blues musicians, a timeless longing for what’s yet to come.

Christopher Cross opened the evening with the understated elegance of a man who dominated the Grammys before Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” changed everything. Cross belongs to that rare category of musicians who, despite commercial success, never quite received the recognition their craft deserved—much like how literary critics only began to truly appreciate Michael Ondaatje after his Booker Prize, even though his earlier works were just as rich.

Cross was accompanied by an outstanding band, akin to a filmmaker who understands that the best cinematographer and editor make the difference between a good story and a classic film. His three backing singers created a vocal tapestry that added an extra dimension to each piece. Lisbet Guldbaek, who once sang in the choir of the great Johnny Hallyday—the French rocker who never conquered America but was bigger than Elvis in Europe—brought a European layering to Cross’s quintessentially American sound.

Vero Bossa, whose voice was once heard alongside the electronic mastery of Jean Michel Jarre and the chanson perfection of Michel Fugain, built a bridge between the American West Coast sound and the European chanson—a cross-pollination that only music can achieve so seamlessly. Then there was Senegalese singer Julia Sarr, who last year released the stunning album “Njaboot,” blending traditional African vocal artistry with contemporary jazz arrangements. Her voice once shared the air with Youssou N’Dour—the man who elevated Peter Gabriel’s ‘In Your Eyes’ to transcendent heights. This vocal triptych coloured Cross’s West Coast yacht rock like a summer palette, rich in nuances that lingered long after the last notes had faded.

At the piano, we heard Jerry Leonide from Mauritius—a name instantly recognized by jazz enthusiasts but still unfairly under the radar for wider audiences, much like when Charles Mingus once said of young Herbie Hancock: ‘He’s already brilliant, but the world doesn’t know it yet.’ Leonide infused the music with his technically gifted, jazz-inspired playing—an approach reminiscent of Keith Jarrett’s fusion of folk and jazz into something greater than the sum of its parts. It was a rare musical blend in pop music, and when it happens, it is always magical—like when Ry Cooder unexpectedly appears on a Rolling Stones track.

It was a true celebration, the kind of musical experience that reminds you why you fell in love with music in the first place—not because of hype or marketing, but because of how certain chord progressions connect directly to something deep within. Alongside “Sailing,” the band played a beautifully crafted but too-short 10-song set, including “All Right,” “Ride Like the Wind,” and “Arthur’s Theme”—songs so familiar they feel like you could have written them yourself. It was a set that transcended the term ‘opening act’—this was a ‘double bill,’ much like Bob Dylan and The Band’s legendary 1974 tour, where audiences witnessed a musical conversation rather than two separate performances.

News had already leaked from Los Angeles: under the musical direction of David Paich, who unfortunately no longer tours due to health reasons, Toto was fine-tuning a refreshed setlist. On this cold February night in a sold-out Mitsubishi Electric Halle, they opened with the orchestral “Child’s Anthem”—a piece European fans hadn’t heard live since 2016. It felt like an old friend, wiser with age.

When “Rosanna” kicked in, we got a masterclass in rhythmic heritage. Shannon Forrest—known to connoisseurs from The Dukes of September, the sublime supergroup with Donald Fagen, Michael McDonald, and Boz Scaggs—achieved something remarkable. He managed to both honour and renew Jeff Porcaro’s legendary shuffle—a feat considering that we’re talking about one of the most respected drum patterns in recorded music history. Forrest brought his jazz-rock sensibility and matured through years of collaboration with blue-eyed soul greats while maintaining the deep groove that made the original so revolutionary.

Journeying through the setlist felt like flipping through a well-worn road map of American craftsmanship. After the final notes of “Rosanna,” “Mindfields” stood as a testament to Toto’s perpetual push to cross boundaries. The late-90s track found a surprisingly natural place among the classics.

The ghosts of rock’s past made their presence felt in moments like these. When Greg Phillinganes sat at his keys, a special warmth filled the audience’s welcome—a collective sigh of relief. The worries from last year, when he suffered a health scare mid-tour in the U.S., seemed far away tonight. His fingers danced across the keys with that unmistakable flair we’ve seen on stage with Michael Jackson and Eric Clapton—a musical gunslinger who has seen it all but still has new stories to tell.

The latest addition to Toto’s lineup, keyboardist Dennis Atlas—recruited from a Styx tribute band, which sounds like the beginning of an unlikely American novel—proved to be a stroke of luck. A gifted keyboardist, but above all, a powerhouse vocalist capable of making audiences forget the late Fergie Frederiksen. During “Carmen,” he astonishingly matched Frederiksen’s soaring highs, proving he was much more than just an impressive player. On “Angel Don’t Cry,” Atlas claimed his spotlight with a performance so commanding it overshadowed the rest of the band—like seeing Rick Wakeman and Lou Gramm fused into one, a rare combination of technical skill and expressive power.

Toto’s backing vocals were exceptional that night. Greg Phillinganes was in top form, reminding us why he has been requested for nearly every monumental tour of the past four decades—he embodies that rare blend of humility and virtuosity that defines the best session musicians. During his solo, he subtly referenced Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s “Hoedown”—a moment the keen-eared audience members surely didn’t miss.

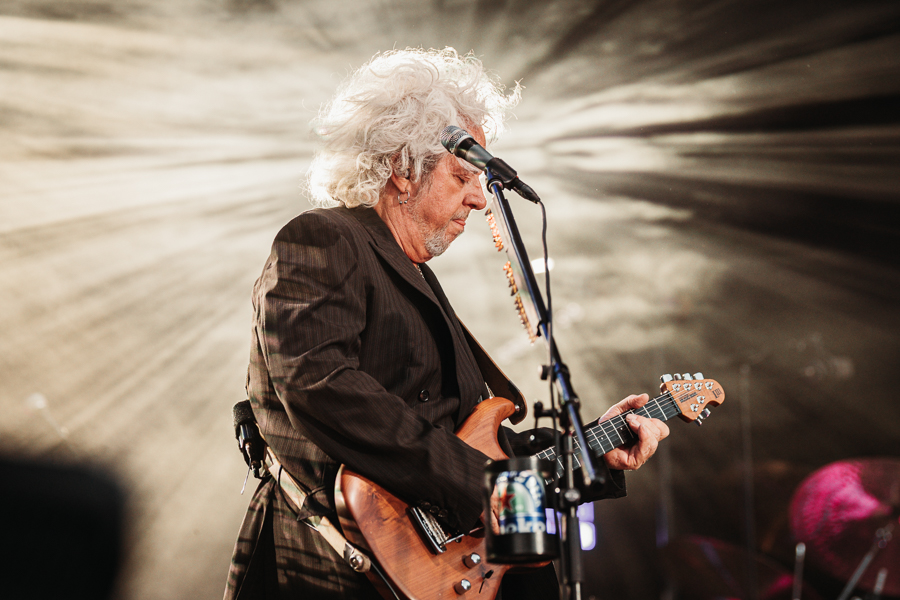

Joseph Williams commanded the stage with an almost defiant energy, his wild curls flowing like a battle flag in the artificial wind of the Mitsubishi Electric Halle. In Toto’s complex history of lead singers—a story marked by both triumph and tragedy—Williams had become more than just a replacement. Since Bobby Kimball’s departure due to illness and Fergie Frederiksen’s passing, he had become the keeper of the flame. His credentials were sealed in the “Fahrenheit” and “The Seventh One” era, but now there was something different about him. The years had given his performance more weight.

As the final moments arrived, Toto played their strongest cards with the practised grace of cardinals conducting a sacred mass. “Hold the Line” and “Africa” were no longer just hits; they were modern anthems woven into the fabric of collective musical memory. The German audience—who have always understood this band better than their American counterparts—rose as one when the first familiar notes rang out.

Tonight was a good performance, though not Toto’s best. Part of that was due to the ageing venue, where no concert can truly sound great—like trying to view a Vermeer under fluorescent light—but also to the fatigue, particularly visible in Steve Lukather. Yet something special lingered in the air, like reconnecting with an old friend and finding that, despite the years, the essence remains unchanged. In an era where so much music feels disposable, Toto reminded us that some things—craftsmanship, dedication, and the sheer joy of musical excellence—never go out of style.