From Gold Rush to Shopping Crush: The Irony of Steely Dan’s “Black Friday”

How a cynical rock song from 1975 became the perfect soundtrack for a phenomenon that didn’t even exist yet—and what it tells us about American obsession, then and now.

Friday, November 28, 2025, somewhere around midnight. In front of the illuminated windows of Best Buy and Walmart, the first campers are gathering, armed with thermoses of coffee and strategic shopping lists. In a few hours, the madness will break loose: Black Friday, the annual ritual where American consumerism shows its most primitive face. Fistfights over flat screens. Trampling at the entrance. Credit cards are melting from overuse.

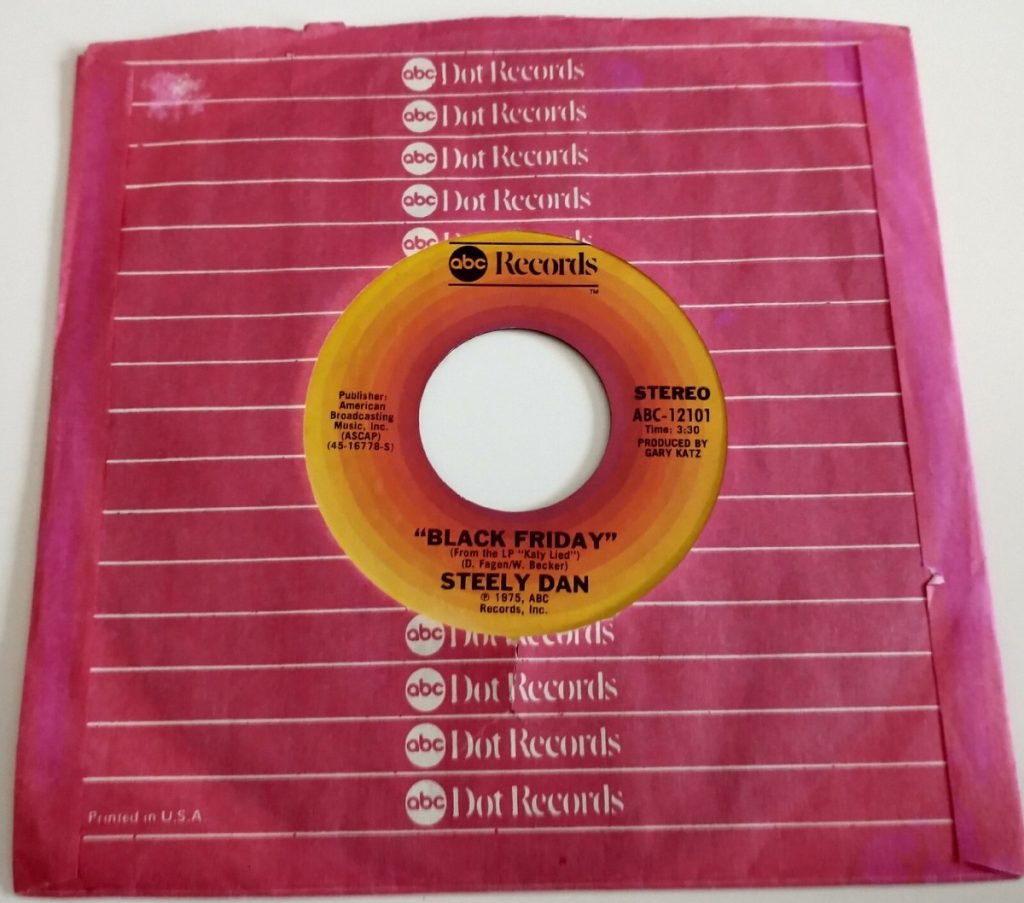

Fifty years ago, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, the cynical masterminds behind Steely Dan, wrote a song called “Black Friday.” It reached a modest #37 on the Billboard Hot 100 in May 1975, then largely disappeared into the background of the Steely Dan repertoire. But here’s the irony: their “Black Friday” is about an entirely different catastrophe—and yet the song, all these decades later, feels like a bitter prophecy of what was to come.

The Other Black Friday

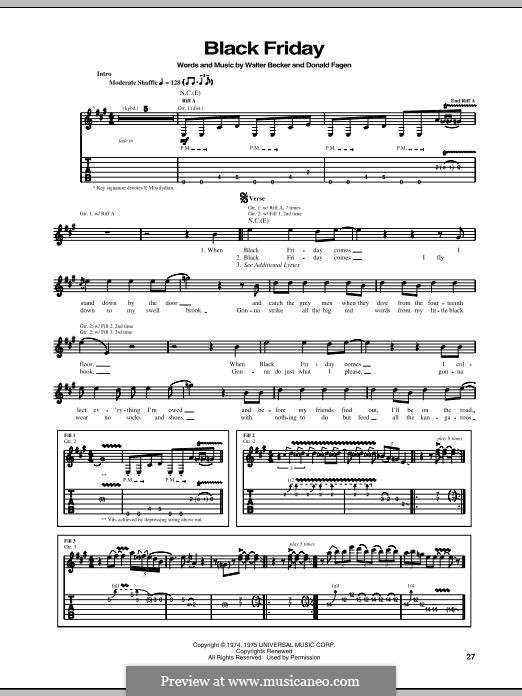

‘When Black Friday comes / I stand down by the door / And catch the grey men when they / Dive from the fourteenth floor,’ Fagen sings in the opening lines. It’s not a metaphor. The song tells the story of the original Black Friday: Friday, September 24, 1869, when the American gold market crashed. Two speculators, Jay Gould and James Fisk, had tried to corner the gold market by buying up as much gold as they could. The price shot up, exactly as planned. Until President Ulysses S. Grant figured out what was going on and promptly dumped four million dollars’ worth of government gold onto the market.

The gold price collapsed. Investors lost everything. The story goes that some literally jumped out of windows—hence those ‘grey men’ who ‘dive from the fourteenth floor.’ In Fagen and Becker’s version of the story, the narrator isn’t one of the losers, but a clever rat who abandons the sinking ship in time: ‘When Black Friday comes / I collect everything I’m owed / And before my friends find out / I’ll be on the road.’

He flees to Muswellbrook, an obscure town in New South Wales, Australia. Why Muswellbrook? ‘It was the place furthest away from LA we could think of,’ Fagen later explained, with that characteristic Steely Dan nonchalance. ‘And of course, it fit the meter of the song and rhymed with book.’ The narrator plans his escape with the same cool calculation you’d use to map out a Black Friday strategy now: which store first, which deals to grab, when to get the hell out before the chaos escalates.

It’s a familiar pattern, really. Grab what you can, stiff your partners, and get out before the reckoning comes. It’s the playbook of every failed speculator and con artist in American history—from Gould and Fisk to the real estate developers who’ve built empires on other people’s money and left a trail of bankruptcies in their wake. Some of them even end up running the country.

Studio Perfectionism and Technical Disasters

Recorded in the winter of 1974-75 at ABC Recording Studios in Los Angeles, “Black Friday” was the opening track of “Katy Lied,” Steely Dan’s fourth album. It was their first record after the definitive break with the original band lineup. Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter and drummer Jim Hodder had left, frustrated by Fagen and Becker’s decision to stop touring and focus entirely on studio work.

What followed was the birth of the Steely Dan model that would become legendary: Fagen and Becker as studio dictators, surrounded by a revolving door of LA’s best session musicians. For “Black Friday” they brought in 20-year-old Jeff Porcaro on drums (who would later form Toto), David Paich on Hohner electric piano, Michael Omartian on acoustic piano, and a young Michael McDonald on backing vocals. Walter Becker played the guitar solo himself—on a Fender Telecaster that happened to belong to Denny Dias, who had left it in the studio.

The song has that characteristic Steely Dan groove: tight, funky, relentlessly propulsive. The electric pianos bounce through the mix like sparks, Porcaro’s drums roll like a well-oiled machine, and Becker’s guitar solo cuts through it all with a kind of nervous, hunted energy—as if the narrator is already halfway out the door with his stolen gold.

But there was a problem. The new dbx noise reduction system in the studio wasn’t functioning properly. According to producer Gary Katz, the material before the mix sounded ‘better than anything you’d ever heard to that date. Even better than “Aja.” Unbelievable.’ But when they went to mix it, the tape sounded ‘funny.’ Fagen and Becker flew to DBX headquarters in Boston to fix the problem. Fixes were attempted, patches applied, but it didn’t remain easy. Becker finally completed the mix at Kendun Recorders.

The duo was so unhappy with the final result that they refused to listen to the completed album—a decision they maintained for decades. The back cover of the original album even featured a half-apology. Ironically, “Katy Lied” sounds crystal clear and brilliantly produced to modern ears, a testament to 1970s studio perfection.

The Transformation of a Disaster Term

Somewhere between 1869 and 1975, the term “Black Friday” underwent a significant shift in its meaning. Retailers in the 1950s and 60s began using the term for the Friday after Thanksgiving—the day they finally got ‘in the black,’ became profitable. Black ink for profit, red ink for loss. It was an accounting celebration, but the name retained that apocalyptic undertone.

When Steely Dan released “Black Friday” in May 1975, the term was already in circulation among retailers, but the mass-hysteria phenomenon we know today had yet to truly explode. Fagen and Becker were writing about 1869, completely unaware that their title would be hijacked within a decade by an entirely different kind of madness. A madness that, if you think about it, isn’t all that different.

The Perfect Cynical Circle

Because that’s the genius irony: both “Black Fridays” are about obsession, greed, and losing control. In 1869, it was speculators who thought they were getting rich and then lost everything. In 2025, it’s shoppers fighting their way to discounts they probably don’t need, on products they’ll forget about in three months. The speculator fleeing to Australia with his stolen gold isn’t so different from the shopper standing in line at 3 AM for a television that’s $200 cheaper.

And here we are in 2025, living in an America that’s turned that grifter mentality into governance. An administration that views government as just another deal to be worked, another opportunity to grab what you can before anyone notices. The same ethic that drove those 1869 speculators—corner the market, manipulate the system, cash out before the crash—has been elevated from Wall Street scam to political philosophy.

Steely Dan built their career on dissecting the American Dream with a scalpel dipped in jazz chords and sardonic humour. They sang about losers, con artists, addicts, and charlatans—the ‘showbiz kids making movies of themselves,’ the ‘razor boys’ with their dark deals. Their America wasn’t a land of opportunity but a film noir landscape of decadent losers, as critic Rob Sheffield once described it: ‘a rock version of Chinatown.’

“Black Friday” fits perfectly into that catalogue. The narrator isn’t a hero but a thief who steals from his friends and makes a quick getaway. ‘Gonna do just what I please / Gonna wear no socks and shoes / With nothing to do but feed all the kangaroos,’ he sings, as if he’s going on vacation rather than fleeing the consequences of his fraud. It’s the kind of moral ambiguity Fagen and Becker loved—no judgments, just observation. And that observation was always: people are crazy, and America makes them crazier.

The song’s narrator promises himself absolution: ‘When Black Friday comes I’m gonna dig myself a hole / Gonna lay down in it ’til I satisfy my soul / Gonna let the world pass by me / The Archbishop’s gonna sanctify me / And if he don’t come across I’m gonna let it roll.’ It’s the con man’s final fantasy—reinvention, redemption without repentance, a clean slate bought with dirty money. Some people call it going to Mar-a-Lago.

A Song for Our Times

If Steely Dan were writing “Black Friday” today, what would change? The fundamentals would remain the same: greed, chaos, people trampling each other for things they don’t need. But the scale has gotten bigger, the stakes higher, the absurdity more pronounced. We’ve gone from speculators cornering the gold market to a political class that treats the entire country like a speculative asset to be stripped and sold.

The beauty of “Black Friday” is that it doesn’t need updating. That nervous groove, that narrator running away with his stolen goods, that underlying panic and greed—it all still works. Porcaro’s drums still sound like the heartbeat of someone making a quick escape. Becker’s guitar solo still has that edge of desperation. Fagen’s cool voice still delivers the lyrics with the perfect amount of detachment, like he’s describing someone else’s catastrophe while already planning his own exit strategy.

The song reached #37 on the charts and then faded into relative obscurity, overshadowed by bigger Steely Dan hits like “Reelin’ in the Years” and “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number.” But it’s aged remarkably well, precisely because the American pathology it describes has never gone away. We just keep finding new ways to express it.

In 2025, as we watch the Trump administration turn federal policy into a family business opportunity, as we see public institutions treated like assets to be liquidated, as we witness the normalisation of corruption on a scale that would make Jay Gould blush, “Black Friday” sounds less like a period piece and more like a documentary. The grey men aren’t jumping from the fourteenth floor anymore—they’re the ones pushing everyone else out the window.

What Would They Think?

You can almost imagine how Fagen and Becker (Becker died in 2017, mercifully spared from seeing how much worse things could get) would react to modern Black Friday—and modern America. Probably with the same dry mockery they brought to everything. They might write a song about a shopper camping out for three days for a new iPhone, full of the same cryptic lyrics and jazzy turns that make “Black Friday” so memorable.

But maybe that song didn’t need to be written. Because “Black Friday” from 1975 already works perfectly as the soundtrack for 2025. That nervous groove, that narrator running away with his stolen goods, that underlying panic and greed—it all fits. The names and dates have changed, but the obsession remains the same. The con remains the same. The fantasy that you can grab everything and face no consequences remains the same.

There’s even a folk singer, Rod MacDonald, who wrote an actual song about the modern Black Friday shopping experience, released on his 2018 album “Beginning Again.” It’s earnest and satirical, perfectly crafted for the folk scene, with lines like ‘Black Friday just ain’t my bag / There’s a fever goin’ round.’ But it doesn’t have the staying power of the Steely Dan original, because Fagen and Becker understood something essential: you don’t need to name the madness to capture it. You just need to describe the mindset that creates it.

The Hill We’re Standing On

‘When Black Friday comes / I’ll be on that hill / You know I will,’ the narrator promises at the end. Fifty years later, we’re all still standing on that hill, watching the circus below, wondering how we got here. Steely Dan knew it in 1975: the obsession with money and stuff isn’t new. It’s just better produced now, with more synthesisers and better special effects.

But the madness? That stays the same. The grift stays the same. The certainty that you can take everything and leave nothing stays the same. Whether it’s 1869 speculators crashing the gold market, 2025 shoppers trampling each other for discounted electronics, or a political class treating democracy like a going-out-of-business sale, the fundamental pathology remains unchanged.

So when you head to the stores this Friday, or decide to stay home and watch the madness on the news, put on Steely Dan’s “Black Friday.” Listen to Porcaro’s drum groove, Becker’s nervous guitar work, and Fagen’s cool voice singing about another kind of catastrophe. And realise that some forms of American madness are timeless—only the details change. The con artist always thinks he’ll make it to Australia before anyone notices. The speculator always believes this time will be different. The crowd always believes the deal is worth the fight.

And the band plays on, sardonic and knowing, already planning their escape route while the rest of us scramble for scraps. Fagen and Becker saw it all coming. They just thought it was funny. The joke, as it turns out, was on all of us.

“Black Friday” can be found on Steely Dan’s album “Katy Lied” (1975, ABC Records). Rod MacDonald’s folk song about the modern Black Friday shopping experience is on his album “Beginning Again” (2018, Blue Flute Music)—proof that fifty years later, it’s still worth singing about.